Researchers at the University of California, Davis, report new information on the mechanism of carbon flow from the Earth’s oceans at the end of the last ice age, based on chemical analyses of the shells of tiny plankton fossils.

“As we alter Earth’s climate by burning oil, gas and coal, we urgently need to understand how the deep ocean sequesters carbon, and how that carbon can flow between the atmosphere and ocean in Earth’s past,” said study co-author Howard Spero, a UC Davis geology professor.

“This study tells us more about the where-and-when mechanics of this cycle, which are still critical questions in climate science.”

Spero’s co-author, Elisabeth Sikes of Rutgers University, will present the findings Monday ( Aug. 30) at the 10th International Conference on Paleoceanography at Scripps Institute of Oceanography in San Diego.

Spero said most experts agree on this general scenario: Marine phytoplankton remove carbon dioxide from the ocean surface, grow, die and sink down into the ocean’s interior, where they are broken down into carbon dioxide by the ocean’s microbial community. (This mechanism is so effective at pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and upper ocean, it’s called the “biological pump.”)

Warm upper water layers form a cap on the cold, deep waters — and the carbon dioxide — somewhat akin to a bottle cap that holds the fizz in a carbonated drink. Deepwater currents move the dissolved carbon dioxide around the planet. Thousands of years pass; glaciers grow, then start to melt.

Eventually, these “old” carbon-rich waters well up to the surface and release their carbon dioxide — a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change — back into the atmosphere.

Where experts diverge is: Where and how quickly does this release occur at the end of an ice age?

Earlier studies suggested that it was spread out over time and place, taking centuries to millennia, and occurring in both the southern and northern hemispheres.

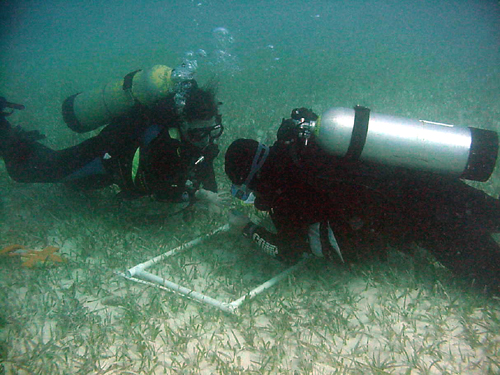

Spero and his colleagues tested that theory by analyzing the carbon-14 content in the fossil shells of tiny sea animals called foraminifera that were living at the end of the last ice age, about 18,000 years ago.

Spero is a leader in using foraminifera to reconstruct Earth’s paleoclimate. The fossil shells, sifted from ancient sediments drilled from beneath the ocean, contain records of the physical and chemical conditions that existed when the animals were alive. Spero previously has used foraminifera to better understand the oceans’ acid-base (pH) balance; correlate temperature shifts in the tropical Pacific Ocean with the birth and death of ice ages; and link the circulation system of the north Atlantic Ocean to salinity levels in the Caribbean Sea.

In the new study, Spero and his colleagues say, the foraminifera carbon-14 data suggest that the carbon dioxide release that preceded the current warm period on Earth was more of a big fizz than a slow leak. It lasted about 6,000 years and took place largely in the icy Southern Ocean (the waters south of 60 degrees south latitude that encircle Antarctica).

This has important implications for understanding where and how carbon dioxide comes out of the ocean — and, especially critical, how fast it comes out.

“We now understand that the Southern Ocean was the fundamental release valve that controlled the flow of carbon dioxide from the ocean to the atmosphere at the end of the last ice age. The resulting atmospheric increase in this greenhouse gas ultimately led to the warm, comfortable climate that human civilization has enjoyed for the past 10,000 years,” Spero concluded.

The two lead authors on the paper are Kathryn Rose, who conducted her master’s degree research in Spero’s UC Davis laboratory and now is a research associate at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Woods Hole, Mass.; and Elisabeth Sikes, a Rutgers University marine scientist. Co-authors are Spero; Tessa Hill, also a UC Davis geology professor; Thomas Guilderson of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory; Phil Shane of the University of Auckland, New Zealand; and Rainer Zahn of Autonomous University of Barcelona, Spain.

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation, Evolving Earth Foundation, Geological Society of America and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Greetings! Is it alright if I go a bit off topic? I’m trying to read your website on my iPad but it doesn’t display properly, do you have any suggestions? Cheers! Chasidy

Hmmm this post is not really good. Can you tell me any related articles?

Thanks for publishing about this. There’s a mass of great tech information on the internet. You’ve got a lot of that info here on your website. I’m impressed – I try to keep a couple blogs fairly current, but it’s a struggle sometimes. You’ve done a great job with this one. How do you do it?

I dig this article. I really learned many things. I’ll ask peers to learn from it too.