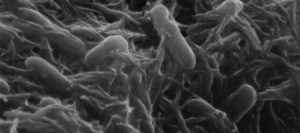

Some bacteria grow electrical hair that lets them link up in big biological circuits, possibly communicating and sharing energy. “This is the first measurement of electron transport along biological nanowires produced by bacteria,” said Mohamed El-Naggar, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at the “University of Southern California.

Some bacteria grow electrical hair that lets them link up in big biological circuits, possibly communicating and sharing energy. “This is the first measurement of electron transport along biological nanowires produced by bacteria,” said Mohamed El-Naggar, assistant professor of physics and astronomy at the “University of Southern California.

He says that the discovery could help find ways to destroy harmful colonies, such as biofilms, and also help with the development of bacterial fuel cells.

“The flow of electrons in various directions is intimately tied to the metabolic status of different parts of the biofilm,” El-Naggar said. “Bacterial nanowires can provide the necessary links for the survival of a microbial circuit.”

To test the conductivity of the nanowires, the researchers grew cultures of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1, a microbe previously discovered by co-author Kenneth Nealson.

The bacteria were then deposited on a surface dotted with microscopic electrodes. When a nanowire fell across two electrodes, it closed the circuit, enabling a flow of current. The conductivity was similar to that of a semiconductor, says the team – modest but significant.

It’s the first time nanowires have been shown to conduct electrons along their length. The researchers point out that Shewanella attach to electron acceptors as well as to each other, forming a colony in which every member should be able to respire through a chain of nanowires.

“This would be basically a community response to transfer electrons,” El-Naggar explained. “It would be a form of cooperative breathing.”

It’s also possible that nanowires may help bacteria to communicate as well as to respire.

Bacterial colonies are known to share information through the slow diffusion of signaling molecules. Nealson reckons that electron transport over nanowires would be faster and preferable for bacteria.