The heat radiating off roadways has long been a factor in explaining why city temperatures are often considerably warmer than nearby suburban or rural areas.

Now a team of engineering researchers from the University of Rhode Island -URI is examining methods of harvesting that solar energy to melt ice, power streetlights, illuminate signs, heat buildings and potentially use it for many other purposes.

“We have mile after mile of asphalt pavement around the country, and in the summer it absorbs a great deal of heat, warming the roads up to 140 degrees or more,” said K. Wayne Lee, URI professor of civil and environmental engineering and the leader of the joint project. “If we can harvest that heat, we can use it for our daily use, save on fossil fuels, and reduce global warming.“

The URI team has identified four potential approaches, from simple to complex, and they are pursuing research projects designed to make each of them a reality.

One of the simplest ideas is to wrap flexible photovoltaic cells around the top of Jersey barriers dividing highways to provide electricity to power streetlights and illuminate road signs. The photovoltaic cells could also be embedded in the roadway between the Jersey barrier and the adjacent rumble strip. “This is a project that could be implemented today because the technology already exists,” said Lee. Since the new generation of solar cells is so flexible, they can be installed so that regardless of the angle of the sun, it will be shining on the cells and generating electricity. A pilot program is progressing for the lamps outside Bliss Hall on campus.”

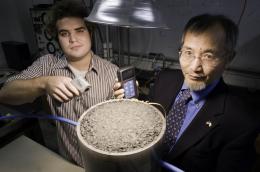

Another practical approach to harvesting solar energy from pavement is to embed water filled pipes beneath the asphalt and allow the sun to warm the water. The heated water could then be piped beneath bridge decks to melt accumulated ice on the surface and reduce the need for road salt. The water could also be piped to nearby buildings to satisfy heating or hot water needs, similar to geothermal heat pumps. It could even be converted to steam to turn a turbine in a small, traditional power plant. Graduate student Andrew Correia has built a prototype of such a system in a URI laboratory to evaluate its effectiveness, thanks to funding from the Korea Institute for Construction Technology. By testing different asphalt mixes and various pipe systems, he hopes to demonstrate that the technology can work in a real world setting. “One property of asphalt is that it retains heat really well,” he said, “so even after the sun goes down the asphalt and the water in the pipes stays warm. My tests showed that during some circumstances, the water even gets hotter than the asphalt.”

A third alternative uses a thermo-electric effect to generate a small but usable amount of electricity. When two types of semiconductors are connected to form a circuit linking a hot and a cold spot, there is a small amount of electricity generated in the circuit. URI Chemistry Professor Sze Yang believes that thermo-electric materials could be embedded in the roadway at different depths – or some could be in sunny areas and others in shade – and the difference in temperature between the materials would generate an electric current. With many of these systems installed in parallel, enough electricity could be generated to defrost roadways or be used for other purposes. Instead of the traditional semiconductors, he proposes to use a family of organic polymeric semiconductors developed at his laboratory that can be fabricated inexpensively as plastic sheets or painted on a flexible plastic sheet. “This is a somewhat futuristic idea, since there isn’t any practical device on the market for doing this, but it has been demonstrated to work in a laboratory,” said Yang. “With enough additional research, I think it can be implemented in the field.”

Perhaps the most futuristic idea the URI team has considered is to completely replace asphalt roadways with roadways made of large, durable electronic blocks that contain photovoltaic cells, LED lights and sensors. The blocks can generate electricity, illuminate the roadway lanes in interchangeable configurations, and provide early warning of the need for maintenance. According to Lee, the technology for this concept exists, but it is extremely expensive. He said that one group in Idaho made a driveway from prototypes of these blocks, and it cost about $100,000. Lee envisions that corporate parking lots may become the first users of this technology before they become practical and economical for roadway use.

“This kind of advanced technology will take time to be accepted by the transportation industries,” Lee said. “But we’ve been using asphalt for our highways for more than 100 years, and pretty soon it will be time for a change.”