Thanks to a little serendipity, researchers at Rice University have created a tiny coaxial cable that is about a thousand times smaller than a human hair and has higher capacitance than previously reported microcapacitors.

The nanocable, which is described this week in Nature Communications, was produced with techniques pioneered in the nascent graphene research field and could be used to build next-generation energy-storage systems. It could also find use in wiring up components of lab-on-a-chip processors, but its discovery is owed partly to chance.

“We didn’t expect to create this when we started,” said study co-author Jun Lou, associate professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at Rice. “At the outset, we were just curious to see what would happen electrically and mechanically if we took small copper wires known as interconnects and covered them with a thin layer of carbon.”

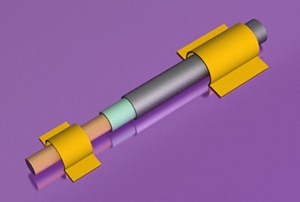

The tiny coaxial cable is remarkably similar in makeup to the ones that carry cable television signals into millions of homes and offices. The heart of the cable is a solid copper wire that is surrounded by a thin sheath of insulating copper oxide. A third layer, another conductor, surrounds that. In the case of TV cables, the third layer is copper again, but in the nanocable it is a thin layer of carbon measuring just a few atoms thick. The coax nanocable is about 100 nanometers, or 100 billionths of a meter, wide.

While the coaxial cable is a mainstay of broadband telecommunications, the three-layer, metal-insulator-metal structure can also be used to build energy-storage devices called capacitors. Unlike batteries, which rely on chemical reactions to both store and supply electricity, capacitors use electrical fields. A capacitor contains two electrical conductors, one negative and the other positive, that are separated by thin layer of insulation. Separating the oppositely charged conductors creates an electrical potential, and that potential increases as the separated charges increase and as the distance between them – occupied by the insulating layer — decreases. The proportion between the charge density and the separating distance is known as capacitance, and it’s the standard measure of efficiency of a capacitor.

The study reports that the capacitance of the nanocable is at least 10 times greater than what would be predicted with classical electrostatics.

“The increase is most likely due to quantum effects that arise because of the small size of the cable,” said study co-author Pulickel Ajayan, Rice’s Benjamin M. and Mary Greenwood Anderson Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science.

Lou’s and Ajayan’s laboratories each specialize in fabricating and studying nanoscale materials and nanodevices that exhibit these types of intriguing quantum effects, but Ajayan and Lou said there was an element of chance to the nanocable discovery.

When the project began 18 months ago, Rice postdoctoral researcher Zheng Liu, the lead co-author of the study, intended to make pure copper wires covered with carbon. The techniques for making the wires, which are just a few nanometers wide, are well-established because the wires are often used as “interconnects” in state-of-the-art electronics. Liu used a technique known as chemical vapor deposition (CVD) to cover the wires with a thin coating of carbon. The CVD technique is also used to grow sheets of single-atom-thick carbon called graphene on films of copper.

“When people make graphene, they usually want to study the graphene and they aren’t very interested in the copper,” Lou said. “It’s just used a platform for making the graphene.”

When Liu ran some electronic tests on his first few samples, the results were far from what he expected.

“We eventually found that a thin layer of copper oxide — which is served as a dielectric layer — was forming between the copper and the carbon,” said Liu.

Upon examining other studies more closely, the team found that a few other scientists had made mention of oxidation occurring on the copper substrates during graphene production.

“It’s fairly well-documented, but we couldn’t find anyone who’d done a detailed examination of the electronic properties of such complex interfaces,” Ajayan said.

The capacitance of the new nanocable is up to 143 microfarads per centimeter squared, better than the best previous results from microcapacitors.

Lou said it may be possible to build a large-scale energy-storage device by arranging millions of the tiny nanocables side by side in large arrays.

“The nanoscale cable might also be used as a transmission line for radio frequency signals at the nanoscale,” Liu said. “This could be useful as a fundamental building block in micro- and nano-sized electromechanical systems like lab-on-a-chip devices.”

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation, Rice University, the Office of Naval Research, the Welch Foundation, the Center for Exotic NanoCarbons at Shinshu University and the Japan Regional Innovation Strategy Program by the Excellence.

Co-authors include Lou, Ajayan, Liu, Yongjie Zhan, Gang Shi, Lulu Ma, Wei Gao and Robert Vajtai, all of Rice University; Pradeep Sharma and Mohamed Gharbi of the University of Houston; Simona Moldovan and Florian Banhart, both of Institut de Physique et Chimie des Matériaux in Strasbourg, France; Li Song of Shinshu University in Nagano, Japan; and Jiaqi Huang, formerly of Rice and currently at Tsinghua University in Beijing.