New research from the University of Pennsylvania demonstrates a more consistent and cost-effective method for making graphene, the atomic-scale material that has promising applications in a variety of fields, and was the subject of the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics.

As explained in a recently published study, a Penn research team was able to create high-quality graphene that is just a single atom thick over 95% of its area, using readily available materials and manufacturing processes that can be scaled up to industrial levels.

“I’m aware of reports of about 90%, so this research is pushing it closer to the ultimate goal, which is 100%,” said the study’s principal investigator, A.T. Charlie Johnson, professor of physics. “We have a vision of a fully industrial process.”

Other team members on the project included postdoctoral fellows Zhengtang Luo and Brett Goldsmith, graduate students Ye Lu and Luke Somers and undergraduate students Daniel Singer and Matthew Berck, all of Penn’s Department of Physics and Astronomy in the School of Arts and Sciences.

The group’s findings were published on Feb. 10 in the journal Chemistry of Materials.

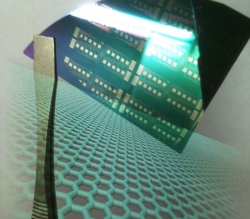

Graphene is a chicken-wire-like lattice of carbon atoms arranged in thin sheets a single atomic layer thick. Its unique physical properties, including unbeatable electrical conductivity, could lead to major advances in solar power, energy storage, computer memory and a host of other technologies. But complicated manufacturing processes and often-unpredictable results currently hamper graphene’s widespread adoption.

Producing graphene at industrial scales isn’t inhibited by the high cost or rarity of natural resources – a small amount of graphene is likely made every time a pencil is used – but rather the ability to make meaningful quantities with consistent thinness.

One of the more promising manufacturing techniques is CVD, or chemical vapor deposition, which involves blowing methane over thin sheets of metal. The carbon atoms in methane form a thin film of graphene on the metal sheets, but the process must be done in a near vacuum to prevent multiple layers of carbon from accumulating into unusable clumps.

The Penn team’s research shows that single-layer-thick graphene can be reliably produced at normal pressures if the metal sheets are smooth enough.

“The fact that this is done at atmospheric pressure makes it possible to produce graphene at a lower cost and in a more flexible way,” Luo, the study’s lead author, said.

Whereas other methods involved meticulously preparing custom copper sheets in a costly process, Johnson’s group used commercially available copper foil in their experiment.

“You could practically buy it at the hardware store,” Johnson said.

Other methods make expensive custom copper sheets in an effort to get them as smooth as possible; defects in the surface cause the graphene to accumulate in unpredictable ways. Instead, Johnson’s group “electropolished” their copper foil, a common industrial technique used in finishing silverware and surgical tools. The polished foil was smooth enough to produce single-layer graphene over 95% of its surface area.

Working with commercially available materials and chemical processes that are already widely used in manufacturing could lower the bar for commercial applications.

“The overall production system is simpler, less expensive, and more flexible” Luo said.

The most important simplification may be the ability to create graphene at ambient pressures, as it would take some potentially costly steps out of future graphene assembly lines.

“If you need to work in high vacuum, you need to worry about getting it into and out of a vacuum chamber without having a leak,” Johnson said. “If you’re working at atmospheric pressure, you can imagine electropolishing the copper, depositing the graphene onto it and then moving it along a conveyor belt to another process in the factory.”