University of Utah physicists invented a new “spintronic” organic light-emitting diode or OLED that promises to be brighter, cheaper and more environmentally friendly than the kinds of LEDs now used in television and computer displays, lighting, traffic lights and numerous electronic devices.

“It’s a completely different technology,” says Z. Valy Vardeny, University of Utah distinguished professor of physics and senior author of a study of the new OLEDs in the July 13, 2012 issue of the journal Science. “These new organic LEDs can be brighter than regular organic LEDs.”

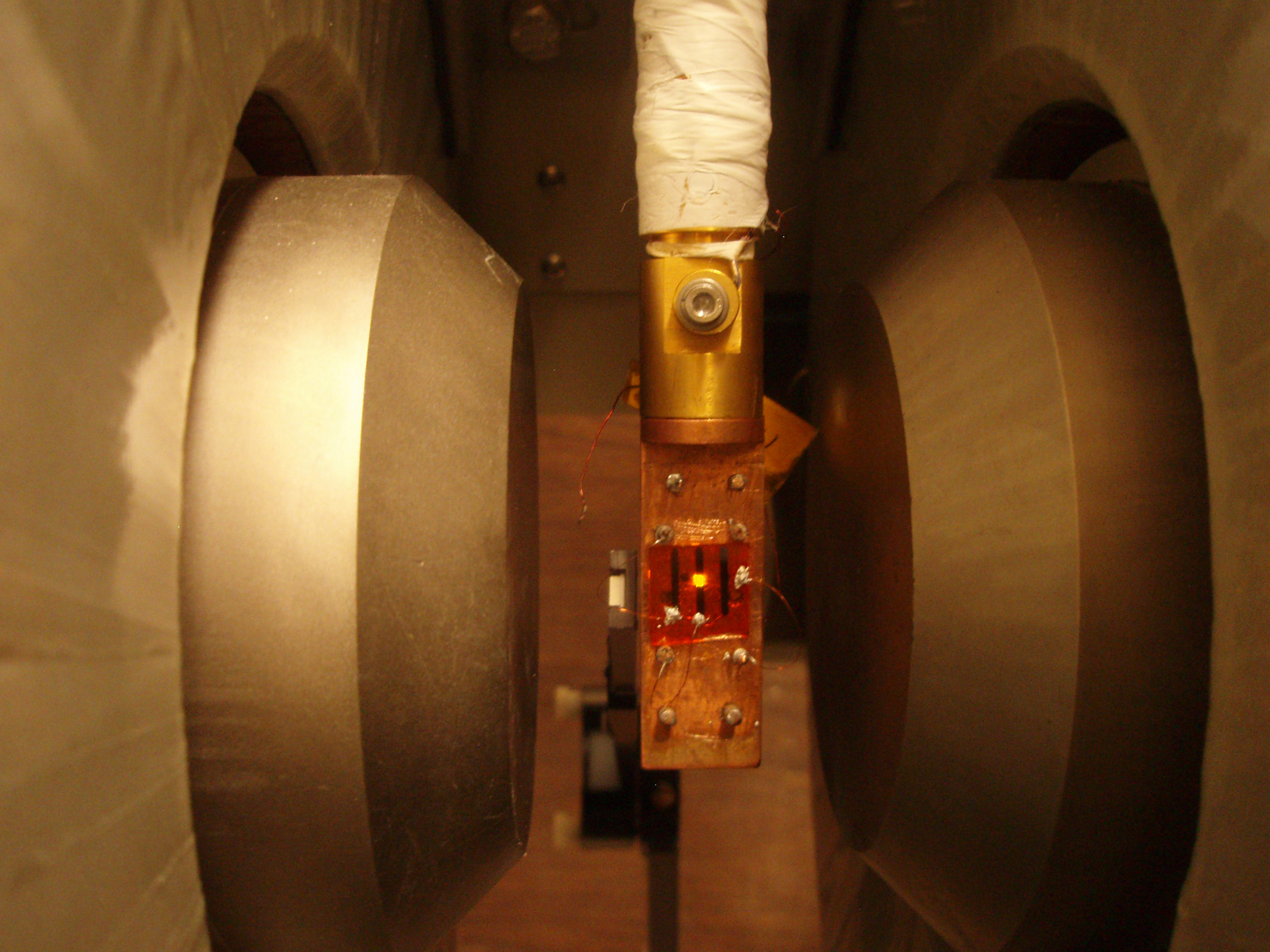

The Utah physicists made a prototype of the new kind of LED – known technically as a spin-polarized organic LED or spin OLED – that produces an orange color. But Vardeny expects it will be possible within two years to use the new technology to produce red and blue as well, and he eventually expects to make white spin OLEDs.

However, it could be five years before the new LEDs hit the market because right now, they operate at temperatures no warmer than about minus 28 degrees Fahrenheit, and must be improved so they can run at room temperature, Vardeny adds.

Vardeny developed the new kind of LED with Tho D. Nguyen, a research assistant professor of physics and first author of the study, and Eitan Ehrenfreund, a physicist at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa.

The study was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy, the Israel Science Foundation and U.S.-Israel Binational Science Foundation. The research was part of the University of Utah’s new Materials Research Science and Engineering Center, funded by the National Science Foundation and the Utah Science Technology and Research initiative.

The Evolution of LEDs and OLEDs

The original kind of LEDs, introduced in the early 1960s, used a conventional semiconductor to generate colored light. Newer organic LEDs or OLEDs – with an organic polymer or “plastic” semiconductor to generate light – have become increasingly common in the last decade, particularly for displays in MP3 music players, cellular phones and digital cameras. OLEDs also are expected to be used increasingly for room lighting. Big-screen TVs with existing OLEDs will hit the market later this year.

The new kind of OLED invented by the Utah physicists also uses an organic semiconductor, but isn’t simply an electronic device that stores information based on the electrical charges of electrons. Instead, it is a “spintronic” device – meaning information also is stored using the “spins” of the electrons.

Invention of the new spin OLED was made possible by another device – an “organic spin valve” – the invention of which Vardeny and colleagues reported in the journal Nature in 2004. The original spin-valve device could only regulate electrical current flow, but the researchers expected they eventually could modify it to also emit light, making the new organic spin valve a spin OLED.

“It took us eight years to accomplish this feat,” Vardeny says.

Spin valves are electrical switches used in computers, TVs, cell phones and many other electrical devices. They are so named because they use a property of electrons called “spin” to transmit information. Spin is defined as the intrinsic angular momentum of a particle. Electron spins can have one of two possible directions, up or down. Up and down can correlate to the zeroes and ones in binary code.

Organic spin valves are comprised of three layers: an organic layer that acts as a semiconductor and is sandwiched between two metal electrodes that are ferromagnets. In the new spin OLED, one of the ferromagnet metal electrodes is made of cobalt and the other one is made of a compound called lanthanum strontium manganese oxide. The organic layer in the new OLED is a polymer known as deuterated-DOO-PPV, which is a semiconductor that emits orange-colored light.

The whole device is 300 microns wide and long – or the width of three to six human hairs – and a mere 40 nanometers thick, which is roughly 1,000 to 2,000 times thinner than a human hair.

A low voltage is used to inject negatively charged electrons and positively charged “electron holes” through the organic semiconductor. When a magnetic field is applied to the electrodes, the spins of the electrons and electron holes in the organic semiconductor can be manipulated to align either parallel or antiparallel.

Two Advances Make New Kind of Organic LEDs Possible

In the new study, the physicists report two crucial advances in the materials used to create “bipolar” organic spin valves that allow the new spin OLED to generate light, rather than just regulate electrical current. Previous organic spin valves could only adjust the flow of electrical current through the valves.

The first big advance was the use deuterium instead of normal hydrogen in the organic layer of the spin valve. Deuterium is “heavy hydrogen” or a hydrogen atom with a neutron added to regular hydrogen’s proton and electron. Vardeny says the use of deuterium made the production of light by the new spin OLED more efficient.

The second advance was the use of an extremely thin layer of lithium fluoride deposited on the cobalt electrode. This layer allows negatively charged electrons to be injected through one side of the spin valve at the same time as positively charged electron holes are injected through the opposite side. That makes the spin valve “bipolar,” unlike older spin valves, into which only holes could be injected.

It is the ability to inject electrons and holes at the same time that allows light to be generated. When an electron combines with a hole, the two cancel each other out and energy is released in the form of light.

“When they meet each other, they form ‘excitons,’ and these excitons give you light,” Vardeny says.

By injecting electrons and holes into the device, it supports more current and has the ability to emit light, he says, adding that the intensity of the new spintronic OLEDs can be a controlled with a magnetic field, while older kinds require more electrical current to boost light intensity.

Existing OLEDs each produce a particular color of light – such as red, green and blue – based on the semiconductor used. Vardeny says the beauty of the new spin OLEDs is that, in the future, a single device may produce different colors when controlled by changes in magnetic field.

He also says devices using organic semiconductors are generally less expensive and are manufactured with less toxic waste than conventional silicon semiconductors.