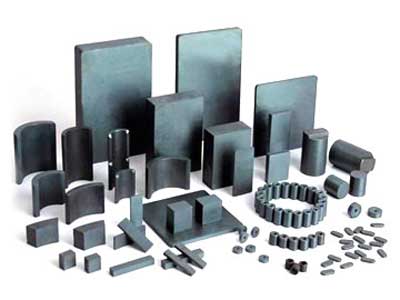

Researchers are now working on new types of nanostructured magnets that would use smaller amounts of rare-earth metals than standard magnets.

Researchers are now working on new types of nanostructured magnets that would use smaller amounts of rare-earth metals than standard magnets.

Many hurdles remain, but GE Global Research hopes to demonstrate new magnet materials within the next two years.

Stronger, lighter magnets could enter the market in the next few years, making more efficient car engines and wind turbines possible. Researchers need the new materials because today’s best magnets use rare-earth metals, whose supply is becoming unreliable even as demand grows.

The strongest magnets rely on an alloy of the rare-earth metal neodymium that also includes iron and boron. Magnet makers sometimes add other rare-earth metals, including dysprosium and terbium, to these magnets to improve their properties. Supplies of all three of these rare earths are at risk because of increasing demand and the possibility that China, which produces most of them, will restrict exports.

However, it’s not clear if the new magnets will get to market before the demand for rare-earth metals exceeds the supply. The U.S. Department of Energy hopes that worldwide production of neodymium oxide, a key ingredient in magnets, will have a total amount of 30,657 tons in 2015. In one of the DOE’s projected scenarios, demand for that metal will be a bit higher than that number in 2015. The DOE’s scenarios involve some guesswork, but the most conservative estimate has demand for neodymium exceeding supply by about 2020.

“A lot of the story about rare earths has focused around China and mining,” says Steven Duclos, manager of material sustainability at GE Global Research. “We believe technology can play a role in addressing this.” The DOE is funding GE’s magnet project, and one led by researchers at the University of Delaware, through the Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E) program, which fosters research into disruptive technology.

Coming up with new magnet materials is not easy, says George Hadjipanayis, chair of the physics and astronomy department at the University of Delaware. Hadjipanayis was involved in the development of neodymium magnets in the 1980s while working at Kollmorgen. “At that time, maybe we all got lucky,” he says of the initial development of neodymium magnets. The way researchers made new magnets in the past was to crystallize alloys and look for new forms with better properties. This approach won’t work going forward. “Neodymium magnet performance has plateaued,” says Frank Johnson, who heads GE’s magnet research program. Hadjipanayis agrees. “The hope now is nanocomposites,” he says.

Nanocomposite magnet materials are made up of nanoparticles of the metals that are found in today’s magnetic alloys. These composites have, for example, neodymium-based nanoparticles mixed with iron-based nanoparticles. These nanostructured regions in the magnet interact in a way that leads to greater magnetic properties than those found in conventional magnetic alloys.